On the Isle of South Uist in the Outer Hebrides, I sometimes hear the word Cailleach (sounds like kayak). It’s used to describe an older woman (not always flattering). The Celtic Goddess or Queen of Winter known as the Cailleach Bheur possessed mana, a presence or a sixth sense. She was also known as the Hag Queen. At first glance this may seem an unkind name, imaging a wizen, elderly woman. However, the word ‘hag’ comes from the Greek hagio meaning holy or saint. Another name associated with Cailleach is witch. The Anglo Saxon word witan means to know – inconsistent with the crazy witch burning phenomenon of 16th century Scotland when the church persecuted women, accusing them of having made a pact with the devil. A hag stone (a stone with holes in) was thought to be sacred; it brought luck and was purported to have healing properties. Sadly, a hag is no longer perceived so well in today’s society.

In Scotland, the Cailleach Bheur was the bearer of storms, frost, snow and winter, inhabiting the mountainous upland. She ruled over the cold, dark months and carried an iron hammer. The Cailleach Bheur is portrayed as elderly, with deathly pale blue skin and long frosted white hair. She was attended by deer and goats. Sir James Frazer, in The Golden Bough, mentions that the last corn cut at harvest is made into a corn dolly or Cailleach which was thought to have secret magical protective powers.

The cold season of the Cailleach Bheur, the transition from Autumn to Winter, takes place at the pre-Christian festival Samhain and Hallowe’en – the eve of Hallowtide. This period includes : All Hallows (October 31st), the Feast of All Saints or All Holy Ones (November 1st) and All Souls Day (November 2nd). Hallowe’en comes from the word hallowed or holy – as used in the Lord’s Prayer: Hallowed be thy name. All Saints Day is a major Church Feast Day and All Souls Day, a time to remember those who have died. A time to visit the graves of the faithful departed.

Eternal rest grant them, O Lord

And let perpetual light shine upon them. Amen

The theme continues to Armistice Day where we remember those who gave their lives in war conflict. Nature’s fields of poppies depict the blood of man.

The Christian Gaels are painted as an innately spiritual bunch, who have happily hung on to folklore customs that others may consider Pagan in tradition. Less well known than Alexander Carmichael and possibly the first scholarly collector of published prayers, charms and blessings, was Alexander MacBain (1855 -1907). A native Gaelic speaker, MacBain believed that Gaelic society had been Christianized relatively recently and sought evidence in Gaelic charms – curiosities remembered from childhood or, at worst, superstitions associated with ‘the evil eye’. Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica is a quintessential work of the Celtic Revival in Scotland, using charms and prayers gathered in the Outer Hebrides and Highlands. Carmichael reported Pagan survivors, but these are deeply knitted with Highland piety – a seeming mixture of rituals. Carmichael collected charms on Uist from 1864 -82. Whilst his Charm collecting was assiduous, on closer investigation, his folklore stories appear to have been gathered in a more ad hoc fashion. In one year his informants consisted of a meagre half dozen or so Islanders.

This said, when researching ‘Seaweed in the Kitchen’, I was enchanted by Carmichael’s inclusion of the of the Sea God Shony. He cites a tale concerning the God fearing people of Ness on the Isle of Lewis: In August each year, the guga hunters’ boats land in the Port of Ness after sailing to the island of Sula Sgeir to hunt for gannets. The Men of Ness have special permission to hunt the guga as a local delicacy.

From a culinary point of view Ness was already on my radar. Carmichael relied not on oral history but the text of the Gael, Martin Martin from Skye, in his book ‘A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland’. Writing in 1703, Martin describes a Hallowtide tradition that took place in St Malvay’s (St Moluag’s) Chapel in Ness. The men gathered, cups of ale in hand, to worship the sea god Seonaidh or Shony. One of the group was chosen to wade into the sea carrying his ale and chant:

Shony, I give you this cup of ale, hoping that you’ll be so kind as to send us plenty of sea-ware for enriching our ground for the ensuring year.

The man then threw the ale into the sea. The use of seaweed as fertiliser is intrinsic to Hebridean crofting (agriculture). The group then went to church where a candle would be burning on the altar. After a few minutes of silence the candle was snuffed out and thereafter everyone enjoyed an evening of merriment. The church ministry (not surprisingly) didn’t appreciate the event and the tradition was halted. Indeed, it may have ceased in the 1630s well before Martin Martin’s documentation. Gifting ale to the Sea God could possibly have been a survivor of pre Reformation Catholicism - i.e. of visiting the chapel on a Feast day. The existence of Shony as a Christian or Pagan God of the elements may be debatable, but there is documentation that Pagan fertility rituals took place at St Moluag’s prior to the 17th century. It is interesting that this story is set in Ness on Lewis, an island where religion, aided by members of The Calvinist Free Church of Scotland, still plays a prominent role in daily life. The Lords Day continues to be observed religiously. The Shony folklore would possibly be more akin to life in the Southern Isles (Uist and Barra), a Catholic heartland, protected from the austerity of Calvinism.

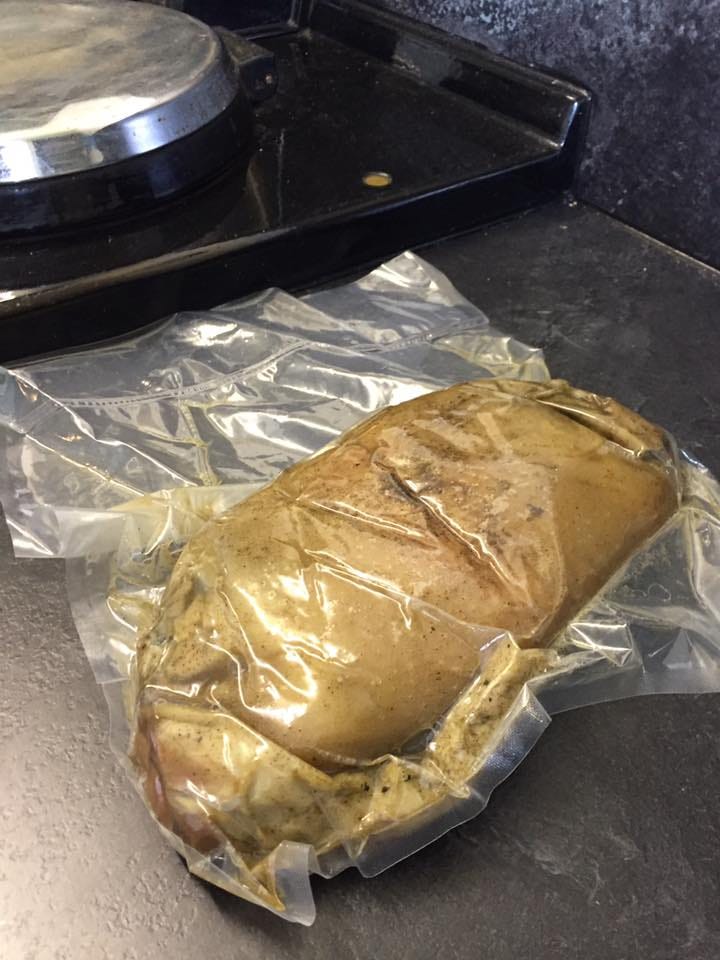

As a seaweed cook, encouraged by the Sea God Shony at Hallowtide, I suggest using dulse in a Hallowe’en Focaccia Recipe. Interestingly this is the time of year (2023) when Crofters take their tractors and trailers to the beach, to gather seaweed to spread on the land.

At Hallowe’en Sir James Frazer writes of children gathering ferns, tar- barrels, furze (gorse) and long thin sedges (gainisg in Gaelic - not to be muddled with the word the word guising – to disguise) and anything else that would burn in a bonfire. This fire festival was known as Samhnagan. The bonfire building was, according to Frazer, a competitive act, with every home ambitious to have the largest fire. Frazer continues: boys would go from house to house begging peat ‘Ge’s a peat t’burn the witches’. The peat was then added to the Samhnagan and the boys lay in front of the fire allowing the peaty smoke to roll over them. In the Outer Hebrides Two nuts were popped into the fire. Each nut represented a person known to the group. As the nuts burned together, flared up alone, or leaped away from each other, there were whispers of marriage or rejection. The fires represented the waning of the power and daylight hours of the westering sun. Hereare some photographs of children guising on South Uist in 1932

Hallowe’en was sometimes referred to as Mischief Night. This was a time for dressing up (guising) and making lighted Jack o’ Lanterns - to drive away evil spirits. A Child born on October 31st was thought to have the second sight. In the old Celtic calendar 31st October was New Year’s Eve. This ties in with remembering those who had died during the year – the Feast of Saints (those who are in heaven and rejoice forever) and the Commemoration of Souls on November 2nd.

A custom of going from house to house saying a prayer for those who had died was known as Souling. Soul cakes, made from an enriched biscuit recipe marked with a cross, were gifted for the souls or spirit of the dead.

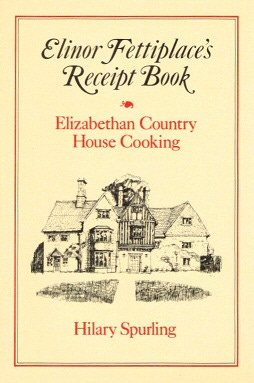

Elinor Fettiplace’s 17th-century recipe

“Take flower & sugar & nutmeg & cloves & mace & sweet butter & sack & a little ale barm, beat your spice & put in your butter & your sack, cold, then work it well all together & make it in little cakes & so bake them, if you will you may put in some saffron into them or fruit.”

The current Trick-or-Treating or Guising (in Scotland) evolved from Souling.

A Soul cake, a soul cake, I pray thee, good mistress, a soul cake.

A soul-cake, a soul-cake. Have mercy on all Christian souls for a soul-cake

A soul, a soul, a soul cake,

Please, good missus, a soul cake,

An apple, a pear, a plum or a cherry,

Any good thing to make us a merry

One for Peter, two for Paul,

Three for Him that made us all.

I’ve got a little pocket, I can put a penny in.

If you haven’t got a penny, a ha’penny will do,

If you haven’t got a ha’penny, then God bless you.

Shakespeare mentions the soul cake in Two Gentleman of Verona

I hope you will prove kind with your apples and strong beer

And we’ll come no more a’souling until this time next year.

One for Peter, one for Paul

One for Him as made us all.

Up with your kettles, and down with your pans

Give us a sou’cake and we will be gone

Some accounts associate soul cakes with alms giving. By this the beggars offered a prayer for the departed in return for a soul cake. This fed the hungry and freed the soul in question from purgatory.

Many old Highland beliefs and customs showing acceptance of the supernatural were woven into the early Celtic faith including the untameable female matrix of fertile healing power with the deep wisdom of the Cailleach. In Gaelic this word also referred to the veil (of mystery) pertaining to married women, including Nuns (who were/are married to Christ). Scottish stories of the Cailleach are wide spread and there are place names connected to her. To the west of the Isle of Shunna is the Cailleach Bheur’s staircase enabling her to cross to Kingairloch.

The Cailleach has a tight grip on the dark months of the Celtic wheel - until it turns on the first day of Spring.

Hallowtide brings the end of Autumn with shortened hours of daylight. The entrance of the next season, winter, is emphasised by the noticeable darkness that occurs as the clocks go back an hour: We welcome Winter and look forward to the First Sunday of Advent and the start of the Church’s Liturgical Year. It is a time to address our fears including that of death. Deciduous tree have shed their leaves, and as we walk through the fallen leaves we remember those who have died, and contemplate our own mortality. The fear behind the guising mask is real as we ‘scry’ (gaze into crystal balls) to fathom the unknown of the future. However, for the Christian, there is assurance of light resplendent and life eternal.

The text from Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8 encourages us to embrace the seasons – ‘There is an appointed time for everything. Each season is unique and with purpose’.

Soul Cakes (adaptation by Fiona Bird)

Makes 15

125g soft butter

125g caster sugar

2 large egg yolks

250g SR flour, sifted

2-3 drops Oil Cassia (or teaspoon mixed spice)

Large pinch ground ginger

75g mixture raisins and currants

Additional caster sugar

Oven 180C

Line two baking sheets with baking parchment.

In a mixing bowl, cream the butter and sugar until fluffy. Beat in the egg yolks and a few drops of oil of Cassia (if using).

Add the flour and spices to the eggs and sugar and gently mix until the flour has blended. Add the dried fruit and gently knead to form a ball.

Lightly flour a working surface and roll the dough to about 1cm in thickness. Use a cut to stamp out 15 Soul Cakes.

Put the cakes on a baking tray and lightly sprinkle with caster sugar. Use a knife to mark each cake with a cross.

Bake for 12-15 minutes. Midway through cooking, carefully remark the crosses.

Leave the Soul Cakes to harden on the tray for five minutes before putting the cakes on a baking tray to cool.

Store in an airtight tin.

Time to reclaim the honourable position of Cailleach, I think - I'd happily volunteer! Lovely post Fiona - such a treat to hear from the Hebrides.

Beautiful reflections, lovely recipes, and such intriguing history. That interaction of old folk customs with Christianity provides for so many fascinating rabbit-holes when trying to follow the threads of tradition back through the mists of history. I was just reading about that curious custom of the Shony ale on Hallowe'en - how interesting to learn more in your piece today!