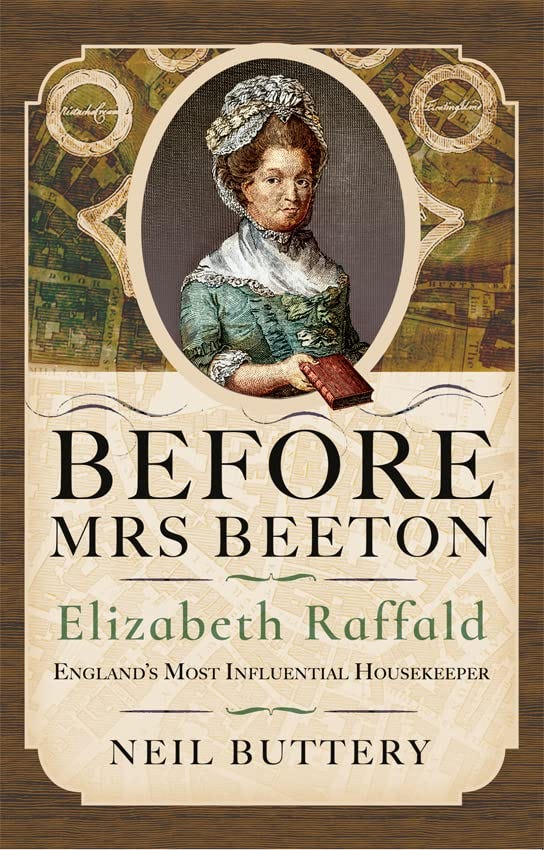

The gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius documented the food of Ancient Rome, but then it wasn’t until the 14th century that the first known English collection of medieval recipes was published – the Forme of Cury. The word cury comes from the Middle French word cuire – to cook. The 1780 printed edition includes 112 meat and 22 recipes of fish or abstinence days. In common with other Medieval cookery books the recipes are rather jumbled. There isn’t a clear index plan. As the centuries passed the illustration in cookery books became more elaborate and by the 18th century there was clear gendered division. Mancunian, Elizabeth Raffald (1733-81) wrote The Experienced English Housekeeper, first published in 1769, with a female audience in mind. Raffald was aware of domestic duty and her recipes acknowledged cooks who lacked time and money.

The audience of a cookery book was apparent by the title, from the professional chef to the home cook. Royal Cookery or the Complete Court Book, by Patrick Lambe (1710) is an example of another sub genre. Hannah Glasse’s 1749 Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy demystified the professional kitchen of the male chef. The word ‘plain’ jumps out of this title. Mrs Beeton’s Household Management (1861) aimed to aid a wide sector of society with reference to: economy, cheaper and plain recipes and even a section on Invalid cookery. There has been criticism of her work, from plagiarism to the exclusivity of her middle class audience i.e. those women who ‘managed’ a household. However, it focused on: order, thrift and cleanliness which would have resonated with the aspirational Victorian middle class.

Following on from the time when it was fashionable for ladies not to know how to cook, came the era of post war cookery books. These books were aimed at the home cook. Such books assumed a female readership. Many of the bestselling books included a manual of manners, perhaps what might be seen as a guide to hospitality as well as cooking. The post war, stay at home mother, had full responsibility for acquiring the art of domesticity. Later, it became acceptable to be Too Busy to Cook and with this came a new genre of ‘time saving’ cookery books The digital age heralded the arrival of the food blog. Food remains at its core, but intrinsic to the narrative is lifestyle. Bloggers often begin with an apology for a period of absence and thereafter offer explanation: my mother has died, I’ve been unwell, I’ve got a new job. Excuses are endless. This enables the blog to move well beyond recipe creation. A blog could be seen as a culinary autobiography - a lifestyle memoir. The blog comment section allows the reader to participate in the ongoing life of the blog. Lifestyle followers span geographical borders as Substack exemplifies. A similar online communication may occur in a digital newspaper cookery column, but it is far more difficult for writers in printed text to enter into dialogue with readers.

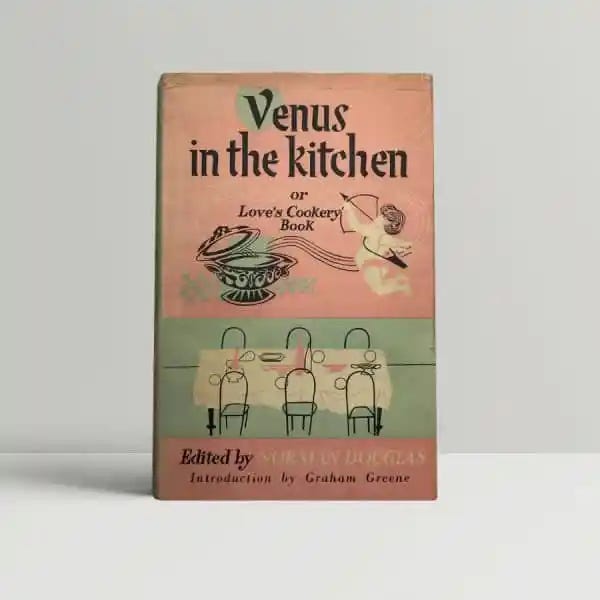

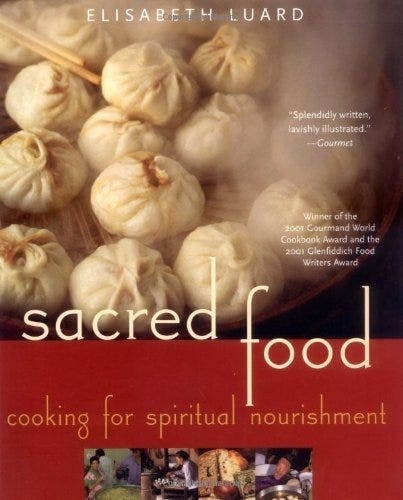

Cookery books are culturally important because they document the daily ordinariness of life and in rural areas especially, the passing of the season. Norman Douglas’ Venus in The Kitchen or Love’s Cookery Book (1952) is a witty collection of aphrodisiac recipes which bring romance into the kitchen. Another collection of love recipes is by Barbara Cartland - The Romance of Food (1984). These cookery book are enchanting books because in common with a romantic novel, they bring fantasy and excitement into the daily routine of preparing food. The British Domestic Goddess, Nigella Lawson brings an added richness in the kitchen. Nigella’s television delivery style is captivating and her recipes work. The writer Elizabeth David (mentored by Norman Douglas) offered post war Britain entry into a fantasy world through interesting ingredients. Rationing made some of David’s recipes inaccessible and for those who did make the purchase olive oil, it was from a chemist not food shop. David brought Mediterranean lifestyle to drab, 1950s Britain. A contemporary British food writer who brings her experiences from living overseas and foraging to the kitchen table is Elisabeth Luard.

I gain an added ‘something’ flicking through the food splashed and pencil scribbled pages of a cookery book when looking for recipe inspiration. Handling the book is part of my recipe hunt experience. Both Elisabeth Luard and Nigella Lawson are prolific food writers - their work is available in print and digitally.

Cookery books tell stories, not necessarily chronologically, but they note a visible record of daily events in the kitchen. Writing down a set of instructions : ingredients, method and cooking time is a literary and scientific exercise. The Doyenne of Scottish Baking Sue Lawrence gave me an excellent tip when she put my name forward for column in The Sunday Post: List Recipe Ingredients In Order of Use. This wee recipe writing nugget is gold dust, it professionalizes recipe writing. The phrase Tested Recipes also gives a cookery book credibility.

With the passing of time cookery books become historical documents, linking generations. Food customs are promoted through recipes - the cookery book is a place for nostalgia, but also of seasonal tradition married into the Church’s Liturgical Year.

Many churches publish cookery books as fundraisers, often including a celebrity recipe in anticipation of higher sales. Some contributors’ recipes hint of ‘showing off’ by requiring unusual ingredients (hard to find), whilst others veer towards the plain or even dull. Yet, each recipe tells its own story. I glance at my late 1980s offering to a charity cookery book and shudder – time consuming with a smack of nouvelle cuisine. Embarrassing. Community cook books are of their era, artefacts of regional cooking at a particular time. All too often there is a plethora of ‘sweet’ contributions in these ‘shared recipe works’. Life is uncertain so perhaps it is okay to eat pudding first, but it doesn’t bode well for an evenly distributed index of recipes. This aside, community books share a love of cooking, local project and friendship as well as the book’s original goal - instruction for food preparation.

The collection of such treasures is usually organised by women. The Ladies of the Scottish Guild undertake this kind of task in my local Kirk. In England it most probably falls to The Mothers’ Union. Whoever is at the church cookery book helm, there is a record of favourite recipes praising God through food domesticity. Publication is by women for women with the church benefiting through funds raised. Women can be united through food as they nurture others. An example of heavily gendered church volunteering. In the story of Mary and Martha, the latter represents home and busyness, ‘to do lists’ (Luke 10 38-42). Mary sat and spent time with Jesus whilst Martha went about the mundane domestic workload thats comes with the role of hostess. The message here is not about the to do list per se, but not feeling aggrieved by domesticity or indeed searching for perfection when there are interruptions to daily routine. Sometimes a quick slap up supper is called for rather than Nouvelle Cuisine.

It is not unknown for a recipe to be a closely guarded secret, demonstrating an unwillingness to share. This does not sit well in a Christian kitchen. Crediting the source of a recipe (even an adaptation) should come naturally, but if commercial money is involved it may become tricky.

There is variation in a recipe: ethnicity, richness, frugality, complexity, simplicity, expense and slow versus fast cooking time. Analysis of a recipe reveals a lot about the social status and culture of the writer. A professional food writer outclasses the amateur who may miss out ingredients or steps in a method, but with enthusiasm the gist of any recipe will hopefully survive. The publishing world has commercial reasons for putting money behind chosen authors but this need not silence the home cook. Each family deserves to own a Treasury of Recipes. In the Christian home it documents ideas for joyful hospitality through Jesus Christ. If young children can be involved there is a learning opportunity (literacy) through recipe reading and writing. A family cookbook signposts change through the generations. It can update social change, modernity e.g. a lower in fat recipe whilst reinforcing the juxtaposition of traditional recipes e.g. Easter Hot Cross Buns and Simnel Cake enriched with foraged and dried seaweed.

A family recipe book allows the writer(s) to reflect on the social and economic conditions of the era - to tweak traditional recipe ingredients so that the recipe reflects a changing world - plant based v animal ingredients. It also provides an opportunity to reconnect with the traditionally female voice in a what can often be a male dominated world. Recipe writing gives credibility to the act of menu planning and enhances the vocation of homemaking. A creative recipe has the potential to reach more people than a rather dull sermon. Feeding family and friends is an important and powerful act. Cooking with real, raw ingredients encourages healthy eating, commensality and can fuel our spiritual thinking.