Oh to visit Japan during the Sakura or cherry blossom season.Such is the importance of Sakura that there are Japanese meteorological forecasts alerting people to the first cherry trees to blossom. Hanami is the name given to cherry blossom tours or put simply ‘viewing blossom’. A myriad of pink flower canopies, symbolise renewal and optimism. The delicate pink petals flutter to the ground like confetti. A sight to behold. Meanwhile, in our Angus garden is an amazing white flowering gean Prunus avium At times this tree, in the words of A. E. Housman wears white for Eastertide.

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

The Angus tree continues to thrive in spite of suffering a battering in a spring storm.We burnt the damaged branches with very heavy hearts.There is a recipe for wild cherry panna cotta in The Forager’s Kitchen Handbook.

The expert phycologist, Kathleen Drew Baker, known in Japan as Mother of the Sea, was born on April 14th 1901.

In 1949 Kathleen Drew published a very brief note in the scientific journal, Nature. The essay was titled Conchocelis-phase in the life-history of Porphyra umbilicalis. Goran Michanek in his bibliographical study of Drew, describes this as 100 lines that should change the world. Kathleen Drew identified the missing link in the life cycle of porphyra (laver). Heteromorphy. This is when something exists in different forms at different stages of development. Prior to Drew’s research the life stages were thought to be two different species. The life history of some seaweed species is complex. Of course, the very fact that development occurs under water makes researching seaweed tricky. Although Kathleen Drew identified the missing link in the life cycle of Laver on the North Wales coast, a Japanese colleague was informed of her research, and the discoveries were passed on to experts working at the Fisheries station in Kumamoto. Kathleen’s findings enabled Fusao Ohta to develop artificial seeding of nori which in turn secured nori harvests. A common name for nori was Gamblers’ Weed because successful harvest was rarely guaranteed. It was indeed a gamble due to destruction of seaweed beds by typhoons and pollution. Drew’s discovery was for the nori farmers of Japan, a life changer and nowadays sushi (rolled nori) is a global food.

Grateful Japanese seaweed farmers contributed to a statue in Kathleen’s honour in Sumiyoshi Shrine Park. This is poignant because on marrying Dr Baker in 1928, Kathleen had to give up her position at Manchester University. In common with Rachel Carson (do read her book Wonder to young children), Kathleen died early, from breast cancer. Perhaps I should plan a trip to the Sumiyoshi shrine when the cherry blossom is in bloom.

‘Scottish laver is not nori,’ Juliet Brodie (Professor of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum) told me authoritatively. ‘It would be like describing English sparkling wine as Champagne.’ In another e-mail Juliet explained that she couldn’t identify my photograph of laver without a microscope. For certain identification one must look at the detailed structure of a species. Prof Mike Guiry tells me that there are 150 species of laver world wide. That’s a lot to identify. Nori Porpyhra yezoensis and Porphyra tenera are cultivated in Japan, the former species making up the bulk of nori. Chatting to Mike Guiry and Juliet Brodie has given me the confidence to use local seaweed names and most importantly, to forage and cook with seaweed. I have found seaweed academics to be approachable and very friendly. I dedicated the revised edition of Seaweed in the Kitchen to Mike Guiry as a thank you. No request however basic was too much bother for Mike. I also gleaned through chatting with academics that botanical names may change. Pom Pom weed is spot on for a child of five, although I confess that the botanical name Ascophollum nodusum has a spell like ring to it. That’s Egg or Knotted Wrack to you and me or perhaps Pop Weed to a child.

Seaweed is stunning and through my seaweeding enthusiam, I’ve met some fascinating people. The South Uist doctor and I spent a jolly, albeit windswept, afternoon with the author of Amy Liptrot and her lovely family, on Easter Monday. Cockling, mussel-ing, popping bladders and a wee taste of the truffle of the sea. Huge gratitude to the local doctor who waded out to gather sea spaghetti.

Meanwhile those of us who chose not to get wet, nibbled on the pepper dulse and gathered laver.I suggested to Amy that laver looks like a crisp, bin liner firmly clad to a rock. Laver has properties that allow it to survive the stresses of low tide and exposure to the elements i.e. sun and wind. As the tide comes in, the laver rehydrates, twice daily. Porphyra is particularly susceptible to drying out because it grows in the intertidal zone. This means that it is exposed to wind and sunshine for longer than subtidal seaweeds i.e. those that are only visible at a low spring tide. A huge amount of laver’s water content is lost when the tide is out. As with all foraging once you get your eye in, you will see this wild edible everywhere. Laver is an easy seaweed to forage because it grows in the accessible, middle shore. You don’t have to don waders (if anyone would like to send me a pair, I’d be delighted), which are helpful when collecting seaweeds in the subtidal zone. Waders could perhaps be on every seaweed forager’s wish list - they are easier to pop on than a wetsuit; perfect for when you think the tide is right and find that the wind has carried water into your wellington boots. A standard experience for me on South Uist. What the Outer Hebridean islands may lack in trees and hedgerow is made up for by its magnificent white, sandy beaches. At low tide an ocean garden is revealed. Here I may gather any amount of red, brown and green seaweeds. Each species has its own unique flavour. Unlike foraging mushrooms, toxicity isn’t a problem, but some seaweeds are tastier than others. Experiment.

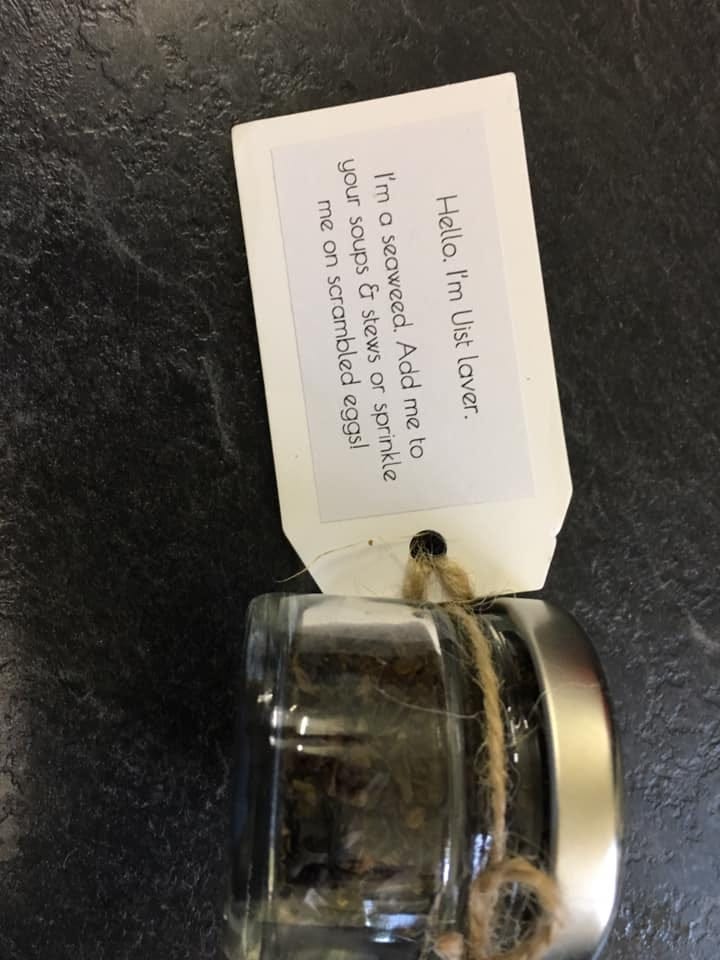

Xander & Lizzie’s Wedding Favour

On National Laver Day – Kathleen Drew Baker’s birthday, forage some laver. Wash well and then spin the laver in a salad spinner. When you think the fronds are clean enough, wash at least one more time because laver harbours sand. You may find a few seaside dwellers too. Pop any visitors into a bucket and re-house at the earliest beach opportunity.

This recipe taken from Seaweed in the Kitchen was kindly contributed by Elisabeth Luard. She writes and illustrates on this platform too. Go find her.

WELSH LAVERBREAD, COCKLE AND BACON PIE

Elisabeth Luard kindly contributed this recipe. If you have foraged,

dried and toasted laver you might like to add 2 tsps of finely ground

laver to the potato pastry.

Serves 3-4

Marine algae: 2 tbsps prepared laverbread

Additional ingredients:

Potato pastry

100g butter, chilled and diced

100g self-raising flour

Pinch salt

150g cold mashed potato

For The Filling

Scrap of butter

2 tablespoons diced bacon

100g prepared cockles or shucked mussels

300ml single cream

4 egg yolks

Salt and pepper

Flour to dust

Set the oven to 200C Gas 6.

Make the pastry. Rub the butter into the flour with the salt

using the tips of your fingers. When the mixture looks like fine

breadcrumbs, work in the potato and knead lightly until you have

a smooth ball of dough. Lightly dust a work surface with four and

roll out the dough to line a buttered (20cm) tart-tin - it won’t need

to rest. Prick with a fork, line with foil and weight with dried beans.

Bake the pastry-case in the pre-heated oven for 10 minutes to set the

pastry, then remove the lining and slip the case back into the oven

for a few minutes for the surface to dry.

Meanwhile, fry the bacon gently in the butter till the fat runs. Add

the shellfish and laver and stir over the heat for just long enough to

heat the laver (don’t let it boil). Whisk the cream with the egg-yolks,

stir in the contents of the pan and season with salt and pepper. When

the pastry case has cooled a little, spoon in the filling. Return the tart

to the oven, lower the heat to 190°C Gas 5, and bake for 35-40 minutes

until lightly set and golden brown (it’ll firm as it cools).

Looking for an illustration of laver and the internet is hopeless/useless. I'm not sure we have it in the northwest Atlantic, although we've plenty of other sea vegetables.

https://www.algaebase.org/search/images/detail/?img_id=14925

I’ll look at Josie Iselin’s The Curious World of Seaweed and email you.Josie and I shared an afternoon at Omnivore Books.